Voice reading of the “SAT as a Privilege Test”:

The SAT is scary. I know it, you know it, we all know it. It’s terrifying to think that a four-hour-long test can hold as much power as it does in one’s future and that it can act as what some may view as the sheer determinant of one’s intelligence. The SAT is a dystopian nightmare, but it’s been painted as an essential component of the college admissions application. And if many colleges and universities continue to use standardized tests in their application cycles, there must be something meritocratic about standardized testing—right?

Want to know more? Read on!

The SAT and Its Correlation To Race

When thinking about race and the SAT, many people already have their own internal biases when they imagine who is scoring well on the SAT and who isn’t. A report analyzing the 2006 SAT, conducted by the College Board, Viji Sathy, Sandra Barbuti, and Krista Mattern (2006), found that many of our internal biases are verified. According to their findings, Asian or Pacific Islanders scored the highest on average on the SAT per each section (Verbal/Critical Reading, Writing, and Math) while Black or African Americans scored the lowest on average.

Advocates against affirmative action policies have noticed this phenomenon and have begun to blame it for the so-called “Asian tax” suggesting that Asians must score substantially higher on the SAT than what many universities expect from other underrepresented minorities. This claim is hard to defend or refute because so much of what happens in the admissions office is a secret. However, Saul Geiser (2015) adds that the racial achievement gap of the SAT is actively decreasing. And though this may sound great at first, he mentions that simultaneously the wealth achievement gap for the SAT is growing.

The SAT and Its Correlation To Wealth

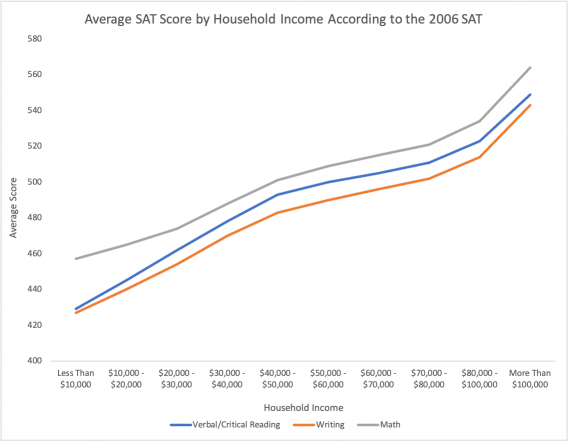

This newly found wealth performance gap has been long backed by data. In the figures collected from the report on the 2006 SAT by the College Board, Viji Sathy, Sandra Barbuti, and Krista Mattern (2006), there was an almost linear, positive correlation between the average score per section of the SAT and household income—don’t be scared, that’s all the math I’ll be using today. This upward trend between household income and average SAT score is mind-boggling! But what I bet you’re wondering right now is: why is this happening?

Figure 1. Average SAT score by household income according to the 2006 SAT reports from data originating from the College Board and Viji Sathy, Sandra Barbuti, and Krista Mattern (2006)

The issue in performance is not because low-income students are dumb or because high-income students are all the reincarnations of Albert Einstein—instead, it has to do with resources. As David Owen (1999) explains, the SAT is extremely coachable and SAT preparation has become a multi-million dollar industry. And because SAT preparation is generally paid for, of course it’s going to be less likely that low-income families will be able to afford test preparation. However, in a system that generally charges students for this sort of SAT tutoring, students belonging to lower-income families are less likely to afford such luxuries. It all comes back to the idea that those who have more cultural capital are able to afford better forms of tutoring and are more likely to have higher SAT scores. However, this does not mean that as a low-income student or any other member of an underrepresented minority group that you should give up—it means that you should fight harder.

So Then What Does the SAT Actually Measure?

I mentioned that there was a racial and financial achievement gap in SAT scores, but the question then becomes: what does the SAT measure? Originally, the SAT used to stand for “Scholastic Aptitude Test,” but ironically they dropped the acronym recently and the test simply has become the “SAT”. According to Krista D. Mattern, Emily J. Shaw, and Frank E. Williams (2008), performance on the SAT is more related to one’s socioeconomic status than their high school grade point average or class rank. They also found that high school grade point averages were a better point of reference to predict an applicant’s college success. Even after years of its existence, the SAT is still not effective at measuring academic preparation—the original reasoning for its implementation in the post-secondary education landscape. In other words, the SAT is stupid, not you.

How to Improve Your Score

Well, it’s all fine and dandy that the SAT is stupid, but many colleges still require the SAT. So, the question then becomes: how does one do well on an outdated test that measures wealth more so than future success in college? It’s good news that students are studying for the SAT and raising their scores—because if they are, why can’t you? The SAT is coachable and this fact is what many SAT college preparation programs and classes bank upon. The following is some advice that we suggest to our students:

- Start early! We suggest starting January of your Junior Year of High School so that you can take the March SAT, the May SAT, and possibly the June SAT. If it’s passed January of your Junior Year, don’t worry—just jump into studying as soon as you can!

- Create a study plan that works for you and find a family member or friend to hold you accountable for it. In Circle Match we have seen great success with juniors taking practice SAT tests in the allotted time every other week, and in between those dates accomplishing at least 10-20 minutes of SAT preparation daily. This may seem like a lot, but the main way to study for the SAT is to practice taking the SAT.

- Utilize Khan Academy’s SAT Preparation. I usually rave about Khan Academy because they have a partnership with the College Board where they offer personalized feedback based off of what you’re getting correct and incorrect while taking practice tests.

- Take the test a second time! The SAT is not fun. Even I, an English major, don’t enjoy reading passages on the SAT about tomato fertilizer (shocking, I know). And though it isn’t fun, in taking the SAT again, you give yourself the opportunity to score higher now that you have taken the SAT already.

And yes, it may feel as if the odds are against you, but the fact that you’re spending your time reading this blog post about the SAT means you care, and that’s the first step! But regardless, no matter what you score on the SAT, remember that you are more than a number, and a score should never and will never define you.

References

Geiser, S. (2015). THE GROWING CORRELATION BETWEEN RACE AND SAT SCORES: New Findings from California. UC Berkeley: Center for Studies in Higher Education.

Mattern, K. D., Shaw, E. J., & Williams, F. E. (2008). Examining the Relationship Between the SAT, High School Measures of Academic Performance, and Socioeconomic Status: Turning Our Attention to the Unit of Analysis(Rep.). The College Board.

Owen, D., Doerr, M. (1999). None of the above: the truth behind the SATs. Rev. and Updated. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Sathy, V., Barbuti, S., & Mattern, K. (2006). The New SAT and Trends in Test Performance (Rep.). New York, NY: The College Board